"I'M A BELIEVER!"

“I’m a believer!” we all sang as we left Alexandra Palace last Thursday lunchtime. We are not always this cheerful, but on this occasion we had reason. For we had just been treated to the Gospel According to the Chief Executive. This Gospel comes from the Book of Local Government, and I don’t doubt it reads pretty similarly to the Book of Higher Education, as recounted by K-Punk recently. We do not live in the most perspicacious of times, it is true, but neoliberalism has managed to come up with its own theological shtick – and it was this Word that was doled out for the benefit of us, the unsuspecting workforce.

I have been to these sort of staff shindigs before, whereby staff are “invited” (on threat of disciplinary action) to meet senior managers, who give us the “opportunity” (in order that they can tick the boxes by which auditors demand that they consult with staff) to “contribute” ideas as to how the Council can move forward (as long as they do not involve harmonisation of pay, lead to greater staff control, or jar with the government’s centralist agenda). Such events are always nauseating and one tends to feel embarrassed on behalf of managers who genuinely appear to believe that they are empowering staff. But this event, billed as a “Smart Listening Forum”or somesuch, was especially dreadful, mainly because, in its exhortation that we enjoy carrying out our duty of kow-towing to our betters (via the usual array of management bullshit “activities” and patting each other on the back), I felt like I was regressing through several stages of human evolution.

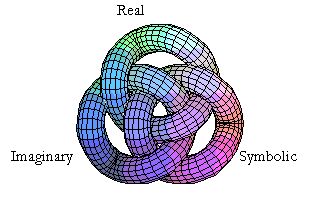

Zizek has described how the superego – that part of the psyche which decides the moral obligations of the ego, and which is thus an intrinsic partner of the Big Other – has altered as a result of society’s increased permissiveness. Once upon a time, received morality dictated that people refrained from doing certain things which would be considered indecent. One did not have homosexual relationships, or extra-marital affairs, or abortions, or talk to your boss as an equal – or rather, one did not do these things openly. (This “one,” by the way, is perhaps the simplest way of thinking about the Big Other – it does not relate to anybody in particular, but it assumes that everybody knows what is and what is not “the done thing.”)

In these postmodern times, there is nothing that we are not allowed to do. Everything is permissible, whether by rules of law or morality. So what happens to the psychical agency of the Law when nothing is illegal? It insists that we must be happy fulfilling our duty.

Now that Viagra can take care of the erection, there is no excuse: you should have sex whenever you can; and if you don’t you should feel guilty. New Ageism, on the other hand, offers a way out of the superego predicament by claiming to recover the spontaneity of our ‘true’ selves. But New Age wisdom, too, relies on the superego imperative: ‘It is your duty to achieve full self-realisation and self-fulfilment, because you can.’ Isn’t this why we often feel that we are being terrorised by the New Age language of liberation?

The Big Other emerges through the Name of the Father, the introduction of language and culture, the imposition of social rules and conventions, the acceptance of the Law. This Lacanian version of the castration complex maintains the possibility of reaching the phallus by deferring its availability, but for both sexes this entails a disclosure of deficiency. An innate lack is thus at the core of the adult subject. In accepting the Law, one must deny one’s most primordial needs lest they be deemed inappropriate, but because it is always “something else” that decides decorum, the ego becomes an empty signifier within a field of language and culture determined by an other. As we will see, capitalism has expertly located this unrealisable lack (which Lacan calls the “objet petit a”) as the source of human desire. It is like a pendulum swinging between the cause of desire and desire itself. The actual concrete object of this desire is somewhat irrelevant, since its attainment could not plug the gap of desire anyway. Paradoxically, capitalism, with all its unfulfilled promises of a better life ahead, is the ideal environment for the perverse human psyche; but it also fuels our appetite for unhappiness.

*

Bill Hicks used to imagine a scene where a newly elected American President would meet the major US industrialist capitalist scumfucks (I think that was the description). The capitalists would show him an old crackly film of the Kennedy assassination taken from a position no-one had ever seen, but which looked to be taken from somewhere off the grassy knoll. The screen would then go black, the lights would come up, the capitalists would puff on their fat cigars and ask the President: “Any questions?”

Clearly the President is not the Big Other: his strings are pulled by the capitalists. So what about the capitalists? Do they create the Law? Clearly not: however tempting (and ethical) it is to despise individual capitalists for their exploitation of the planet, they are merely following the demands of capitalist logic. This is why the post-Socialist left is unable to erode capital’s framework: it is amorphous, impersonal, “worldless.”

Lacan located desire as being the demand for attention or love minus its immediate satisfaction; it is “the ephemeral, unlocalisable property of an object that makes it especially desirable.” As I hinted above, capitalism works on this principle too: its inexorable progress is the sum of its demand for profit minus the actual profit made. In other words, no amount of profit will ever prevent a capitalist from demanding more.

And we can see how the lack that creates desire might have created capitalism in the first place. In order to fill his immanent shortcomings, man felt the need to explore the world, to gain greater knowledge, to become master of the world. The Enlightenment manifested this desire in science, the arts, philosophy, religion etc, but it also entailed the discovery and mastery of other lands. Imperialism and capitalism were, therefore, inevitable results of the Enlightenment, of which the human “ache of desire” is the source.

This leaves the Big Other in something of a pretty pass. As Zizek notes in the article I link to above, the social regulations of the Ten Commandments – thou shalt not kill, thou shalt not steal, thou shalt not lie – have been replaced by the primacy of the self (the right to bear arms, the right to private property, freedom of expression). The Big Other has acted upon itself by subverting its own laws, yet the centrality of these new so-called “human rights” (and their economic equivalent, the primacy of individual entrepreneurialism instead of public ownership) require even greater central control. This is why K-Punk is having a probe stuck into every orifice of his Department, why there is a CCTV camera on every street, and why the World Bank must constantly intervene in order to maintain its preferred “laissez-faire” economic model. One can see how the Big Other, far from being stable, is like the pendulum Lacan uses to describe the objet petit a.

So how might we stop the pendulum mid-swing? If the Big Other has become increasingly reflexive in our post-modern, might we use this reflexivity for our own ends? During his Birkbeck lecture last week, Zizek told a story about his student magazine in Slovenia during the early 1980s. It was election time, and the Communists were obviously going to win again. Instead of pointing out that the election would be rigged, the magazine went along with charade. In a late edition, the headline read: “LATEST: COMMUNISTS EXPECTED TO WIN AGAIN.” When challenged, Zizek and his colleagues pleaded ignorance, but the authorities knew their Achilles heel had been exposed. Capitalism is subtler in its tricks than Communism was; our trick is to expose its Achilles heel by following its logic to its most absurd conclusion.