SIX INITIAL THOUGHTS FROM BOLIVIA

1.

I hadn`t planned to cross the border into Bolivia last Thursday evening. I had wanted to savour one last Argentinian meal, one last night in an Argentinian bed. But I met a guy on the bus from Jujuy in north-west Argentina, and as the bus ascended to 2,000, 2,500, 3,000 metres above sea level, the thrill of the altitude hit us and we decided we would catch a connecting bus from the Argentinian-Bolivian border town of Villazon to the town of Tupiza, where Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid robbed their last bank.

In Villazon we met an Israeli couple, and the four of us caught a bone-rattling bus on which we travelled the two hour long bumpy ride to Tupiza. Buses in Bolivia, even those which purport to be 5-star buses, are fairly creaky machines, rejects from the USA. When such a bus is driven on a dirt road (only the most major roads in Bolivia are covered with asphalt), you should expect a fairly jarring ride.

2.

In the Argentinian city of Salta, I had been warned not to go to Bolivia. Two weeks or so ago, trouble broke out in the central Bolivian city of Cochabamba. Supporters of President Evo Morales took to the streets in a protest to demand the resignation of Manfred Reyes Villa, the conservative governor of Cochabamba. The protest began peacefully enough, but soon turned violent, with two people from each side of the battle being killed.

In its page about Evo, Wikipedia describes the cause of the uprising in Cochabamba :

In January, Evo tried to force (citation needed) the Governor of Cochabamba Reyes-Villa, to resign due to his opposing views regarding the economy (citation needed). The Governor of Cochabamba, who had recently been democratically elected by a majority of the popular vote in the state, refused to step down unless the people who voted for him asked him to do so, and this triggered widespread support for the governor (citation needed). Morales sent irregular forces (citation needed) to quell the support and force the Governor to resign. Supported by Venezuelan advisors (citation needed) the cocaleros laid seige to the city, cutting off the airport, all roads, and forcing the local government to take refuge in a hotel. This caused the governors supporters to take to the street and defend their elected official, in turn the irregular forces were armed with machetes and sticks (citation needed). Radio broadcasts were transmitted and small battles erupted leaving at least 2 dead and over 100 injured.

You may have guessed from the quantity of citations needed that this account may be biased ; in fact, it is fabulously inaccurate, a pack of lies from start to finish. Evo did not try to force Manfred from power ; Manfred´s actions in the past few weeks have made him extremely unpopular ; Evo did not send in "irregular forces" ; and it was Manfred´s supporters who were armed with baseball bats, and who were smashing the shit out of elderly coca growers.

MANFRED REYES-VILLA´S ARMED SUPPORTERS BEGIN THEIR STAMPEDE

The real issue here is who stands to gain from Bolivia´s rich, and recently re-nationalised, mineral resources. Bolivia has been described as a beggar sitting on a goldmine. Its oilfields are the second most profitable in South America (after Venezuela), and yet Bolivia has had the lowest GDP of any country in the continent for many years. Bolivia´s GDP currently stands at around $2,700. Internationally, it is slightly lower than Angola and slightly higher than Pakistan, and there are 125 countries in the world which are richer. Why has Bolivia not realised its economic potential for so long?

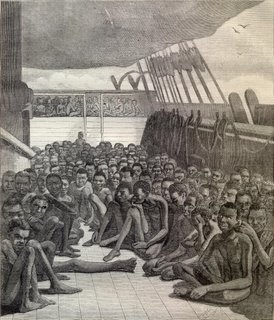

Both the distant and the recent past suggest that this is because the profits made from its resources (whether silver from Potosi in the western altiplano, or oil from the eastern lowlands) have not stayed in Bolivia. We have already seen how indigenous and African slaves were worked to death in the 16th century to provide riches for the Spanish crown. But during the 1980s and 1990s, Bolivia was forced to privatise many of its natural resources in return for foreign aid, and state companies were sold to private corporations for absurdly low prices. I will go into much more depth on this in the next month or so.

In January 2005, after two or three years of fierce opposition to the neoliberal policies that had crippled Bolivia´s economy, Evo Morales was sworn in as President - the first indigenous President in the history of Latin America. Evo won the election, the first President to be elected by the people for many years, gaining over 50% of the vote. His victory was primarily the result of two pledges : to re-nationalise those resources which had been sold off by previous governments, and to re-write the constitution to give more power to indigenous people, who despite being a majority, have traditionally been marginalised from the political process. (A third important pledge was to increase GDP by confiscating private land which was not being used productively - 80% of the land in Santa Cruz is owned by just 14 families, many of whom do not live in Bolivia) In his first year, Evo has carried out the first pledge, and is making some (though limited) progress with the second.

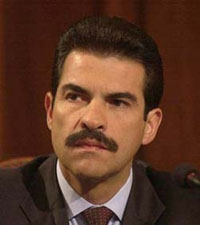

PRESIDENT EVO MORALES

But anyone who thought that such a dramatic shift in ideology - away from the IMF/World Bank appeasing policies of his predecessors towards a more socialist approach, specific to Bolivia - was going to be painless and seamless, would have been badly mistaken. The conservative elite may not be in government anymore, but they have not gone away. Whereas Evo and his Movimiento al Socialismo party believe that theirs is a revolutionary government, in power to liberate Bolivia from hundreds of years of imperialism, their opponents see MAS as just another government. MAS sees itself as sowing the seeds of a new era of Bolivian socialism ; the right-wing believes that its time will come around again, and that the country is just going through a temporary (if regrettable) blip.

Which side is correct remains to be seen, but the unrest in Cochabamba in January was a sign of both sides flexing their muscles. The furore was provoked, contrary to the claims of Wikipedia, by Manfred Reyes Villa, the conservative governor of the Cochabamba Department calling for regional autonomy. The issue of autonomy comes down (as it does in Iraq) to oil. The eastern Departments of Bolivia are the richest in oil, and there is a wing of politicans and business people who believe that autonomy would mean that their departments would not need to share their wealth with the Departments in the western altiplano. They are, of course, correct ; but the voters of Cochabamba have already rejected this vision : in 2006, a large majority of Cochabambinos voted "no" to autonomy.

MANFRED REYES VILLA, GOVERNOR OF COCHABAMBA PROVINCE (a.k.a. Officer Crabtree from ´Allo ´Allo)

Those voters saw Manfred´s interjection as interfering and undemocratic, and many travelled to the city of Cochabamba to demand that their governor resign. These demonstrations were largely peaceful, and aimed at disrupting the city via blockades rather than violence. But then, a day or so later, Manfred´s supporters turned up, armed with baseball bats :

The pro-Manfred march had been billed as peaceful, and there were reasonable, non-violent people who participated in it. But the contingent at the front of the crowd evidently had something else in mind. They didn’t march toward the campesinos in the style, even, of an aggressive protest. Once through the police line, either acting on plans made beforehand or giving in to the angry chaos of the moment, they launched an assault that bore no resemblance to civil protest.

I saw men using their sticks to threaten young and middle-aged campesinas—even one with a child on her back—yelling at them. Expressions of terror flashed on the faces of the women. One campesina, pursued by marchers, fled into the gated front yard of a nearby establishment. The person guarding the gate shut it behind her. A crowd gathered around yelling at her. They dispersed when someone behind the gate escorted her safely out of sight.

The police continued shielding the injured with their own bodies until each person was safely inside an ambulance or a truck. At one point, they had to hold a small crowd of yelling pro-Manfred supporters back from a campesino man on a stretcher. My Spanish is not good enough to know exactly what was being yelled at the campesinos out in the crowd, but I made out one statement hollered by my very own neighbor at an injured man: “Go home, Indian!”

Even a man whose face was a river of blood—whose T-shirt was soaked-through so that the entire front of it was crimson, whose eyes were foggy with shock—was yelled at as he staggered by dripping a trail of blood.

- Eyewitness account from Jonas Brown, a resident of Cochabamba.

Two people - one campesino, and one young supporter of Manfred - were killed in the violence, with many more badly injured.

After these days of violence, Evo and Manfred (whom were both absent from Cochabamba at the time of the riots) took stock. Evo returned from Daniel Ortega´s Presidential inauguration in Nicaragua and said he would not push for Manfred to be ousted. Manfred, who had not improved his reputation by exiling himself himself in another city (Santa Cruz) during the violence, stated that he would not push for a re-vote on autonomy.

However horrible the violence was, none of this means that Bolivia is on the brink of civil war. Bolivia is beginning a new chapter of its history - a chapter in which itis attempting to wrest control back from international authorities and corporations. Such a genesis was never going to be painless, and Evo has done well to make the progress that he has. For the first time in many years, Bolivia is now running a budget surplus, and the salaries of many public sector workers (especially teachers) have jumped as a result of increased revenues following subsoil hydrocarbon renationalisation. It is also true that Evo can be his own worst enemy - he has alienated many of Bolivia´s non-indigenous people by not really including them in his plans for the new Bolivia ; and his first anniversary State of the Nation address last week went on for a portentous four hours.

From what I have seen, though, Evo has nursed a remarkably smooth birth of a new Bolivia, which stands with Venezuela and, recently, Ecuador as an alternative to neoliberalism. It should be hoped that Cochabamba is not a sign of things to come, for in general political disputes between normal people have been carried out with the enthusiasm of a country searching for a better future. If only the West could enjoy such lively political debate, perhaps some of their countries would not be stuck in the quagmire of Iraq right now. Moreover, as US Professor Newton Garner has pointed out, violence is tactically, as well as morally, undesirable :

Violent confrontation would suit the rich elite, for they are rich enough to win a show of force. Violent confrontations also stall the economy, and if there is to be greater equality in Bolivia it must come from greater wealth, not through dividing existing wealth.

For more on Bolivia, Venezuela and South America in general, see here.

3.

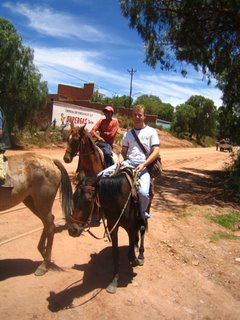

My first morning on Bolivian soil was spent on the back of a horse named Calypso. Calypso and I did hit it off at first ; the guide gave me his most tranquilo horse, but for the first hour Calypso barely broke into a trot. In fact, I told him in no uncertain terms that I thought he was rather lazy. Everytime we passed a patch of grass, which even in the earthy south-west of Bolivia was often, Calypso ground to a halt, had a snack, and took a siesta. When he saw the guide glaring at him as if he was a miscreant child, he sped up a bit, but suffice to say that I lingered at the back of the group for most of the outbound journey.

PADDINGTON´S OFFICIAL SPOKESPERSON, ABOUT TO FALL OFF HIS HORSE

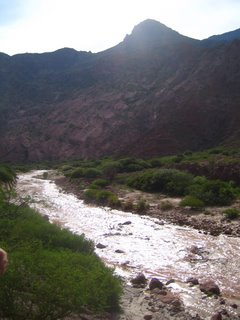

At least Calypso´s pace (or lack thereof) enabled me to soak up the landscapes. Brick-red cliffs and jagged rocks strike out from a burned and thirsty floor, from which uncompromising scrubs of grass grow ; and all is covered by a brilliant blue sky. The colours of the landscape - and the sky - have changed regularly during my first week here : within a day the extreme colours of Tupiza had given way to pastel greys and pinks and browns, as we climbed several kilometres above sea level. But for now, we cantered through vivid technicolor. And on the way back, Calypso decided he was bored of cantering and suddenly bolted into a furious gallop. I nearly fell off his back on several occasions, and whether I will ever be able to have children remains to be seen ; but Calypso and I parted on friendly terms. I thanked him in my best Spanish for such an energetic ride, and he replied with a courteous snort.

PUERTA DEL DIABLO (THE DEVIL´S DOOR) - TUPIZA, BOLIVIA

4.

The following day, six of us - two Argentinian artists, a Dutch-Iranian dancer, an Israeli couple, and myself - set off in a jeep from Tupiza on a four-day excursion around the south-western altiplano. After a long drive into the mountains, we arrived at our first hostel just as the sun was beginning to set. It was in the middle of nowhere, without hot water or electricity. The lack of light and the cloudless sky gave us the second-best night sky I have ever seen - a mass of pitch-black, dotted with pinpricks of white, hinting at a brilliant universe beyond our own. Since we had to be up at 5am the following day, and since it was too cold (even in my new llama-wool hat and gloves) to watch the sky for long, we all had an early night and lulled ourselves to sleep with songs (a Persian folk-song, an Israeli children´s song, and a tango duet). Fear not, dear readers, for I did not partake in the singing. I told the first chapter of my novel, and then attempted to translate what I had just related into Spanish. Everybody was so baffled, they fell asleep immediately.

You can only travel round the extreme south-west of Bolivia via an organised excursion. To do it off your own back would be insane. All the roads are dirt-tracks, most are upwards of 4km above sea-level, and some of the ground is so harsh that only the hardy pajabravo ("brave straw") can survive there. But among the scrubby, wild-west mountains and volcanoes, and the dadesque rock formations, there are places of astonishing beauty - lagunas coloured green and red by mineral deposits and plankton. These lagunas are home to flocks and flocks and flocks of pink and white flamingos. But enough of my guff : a few photos will tell the story much better.

FRUIT AND VEGETABLE MARKET IN TUPIZA

LAGUNA VERDE (THE GREEN LAKE)

FLAMINGOS ON LAGUNA COLORADO

EL ARBOL DE PIEDRA (THE STONE TREE)

5.

This salt

in the saltcellar

I once saw in the salt mines.

I know

you won't

believe me,

but

it sings,

salt sings, the skin

of the salt mines

sings

with a mouth smothered

by the earth.

I shivered in those

solitudes

when I heard

the voice

of

the salt

in the desert.

Near Antofagasta

the nitrous

pampa

resounds:

a

broken

voice,

a mournful

song.

In its caves

the salt moans, mountain

of buried light,

translucent cathedral,

crystal of the sea, oblivion

of the waves.

And then on every table

in the world,

salt,

we see your piquant

powder

sprinkling

vital light

upon

our food.

Preserver

of the ancient

holds of ships,

discoverer

on

the high seas,

earliest

sailor

of the unknown, shifting

byways of the foam.

Dust of the sea, in you

the tongue receives a kiss

from ocean night:

taste imparts to every seasoned

dish your ocean essence;

the smallest,

miniature

wave from the saltcellar

reveals to us more than domestic whiteness;

in it, we taste infinitude.

- Pablo Neruda, "Ode to Salt"

SUNRISE OVER THE SALAR DE UYUNI

THE SALAR, EARLY MORNING