ADAPTATIONS

The first time one watches Mulholland Drive, one initially sees the efforts of a young, cute-as-pie actress named Betty and her mysterious new friend Rita, who is amnesiac as a result of a car crash, try and discover Rita's true identity. Betty goes to an audition for a minor picture and carries off an extraordinary performance, transforming herself from a saccharine all-American kid into a mistress of seduction. An agent, who happens to be sitting in on the audition, is so impressed that she takes Betty to another audition, this time with a major director, Adam Kesher. Their eyes meet across the studio, but Betty is gazumped : the mob have terrorised Adam into casting a vacuous bombshell called Camilla Rhodes.

After the Club Silencio scene, where various acts lip-synch to music, each act becoming more intensely "real" than the last, the film turns into what seems like a nightmare. Betty has turned into Diane (the name they had previously assumed was Rita's, and whose dead body they believe they have just found) and is now depressed and out of work ; and Rita has turned into Camilla, a successful actress who is about to marry Adam. Diane and Camilla are having a sexual affair, though it appears that Diane loves Camilla, whereas Camilla wants to call the affair off. Finally, fizzing with jealousy, Diane arranges to have Camilla killed and, racked by guilt and lost innocence, kills herself.

One's immediate impression might be that Diane and Betty are aspects of each other, and that Rita and Camilla are aspects of each other ; but one will probably be unable to resolve how this can be, how what one has just seen "fits". One will go to bed extremely confused. The next morning, one will look Mulholland Drive up on Wikipedia, follow the links to various reviews and explanations, and discover that the Betty-Rita section of the film is a dream, a wish-fulfilling prequel to the frightening reality of the last third. It will be explained that minor events in the "real" final section (such as the man who glares at Diane at Rita and Adam's party on Mulholland Drive, or the cowboy) take on a mythical significance in the "fantasy" element (as the espresso-spitting mafioso, and the criminal Big Other respectively), just as happens in regular dreams. All the bits that didn't make sense at first suddenly fall into place. You may watch Mulholland Drive again, but only to say "Ah, of course!" at all the bits you missed first time round.

But isn't all this a bit straightforward? Couldn't we just as easily say that the first two thirds is "reality" and the last third a death-driven "fantasy"? A different "message" would emerge of course : rather than people who live complicated lives retroactively trying to clarify their actions, we would have a person who lived a superficially great life, but lived a horrible, haunted, nightmarish life outside the metaphorical view of others. To claim that one part is "dream" and one part "real life" is to assume that fantasy and reality are two mutually separate areas of the psychical domain.

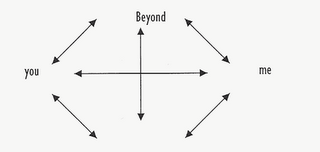

We might recall (for we probably all know such people) the macho man who finds sex difficult ; or the quiet, mousy guy who creates and performs fantastic sexual acts. Which one is the macho man? Which is the shrinking violet? We cannot be so crude as to say. We swing like a pendulum between different shades of fantasy and reality from one minute to the next. Or, as Lacan put it, "truth has the structure of a fiction." And what is more, we cannot even be so precise as to say : "Ah, well I adopt a certain identity in the office, and another in the bedroom." For "me" to be able to choose between them would assume that actually "I" am neither, and instead occupy a quasi-divine position whereby, having created these masks, I can choose which one to put on. In fact, these personas have created you. And this, my friends, is called dialectical materialism.

Anyway, with this in mind, I have been re-listening to Bryan Ferry's These Foolish Things, the debut solo album released in 1973. Like Bowie's Diamond Dogs from the same year, it is entirely covers of (unlike DD, mostly American) standards. You can see the link here, however tortuous : in living out our daily lives, we constantly "cover" ourselves, think of ways to reinterpret ourselves.

The track listing of These Foolish Things is as follows :

"A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall" (Bob Dylan)

"River of Salt" (Kitty Lester)

"Don't Ever Change" (The Crickets)

"Piece of My Heart" (Erma Franklin)

"Baby I Don't Care" (Elvis Presley)

"It's My Party" (Lesley Gore)

"Don't Worry Baby" (The Beach Boys)

"Sympathy for the Devil" (The Rolling Stones)

"The Track of My Tears" (Smokey Robinson and the Miracles)

"You Won't See Me" (The Beatles)

"I Love How You Love Me" (Paris Sisters)

"Loving You Is Sweeter Than Ever" (Four Tops)

"These Foolish Things" (Dorothy Dickson)

(with the artists who made those songs their own in brackets, of course)

You can find the video for "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall" on Youtube : it is just devastating. It turns an organic song written specifically about the threat of nuclear war in 1963 - a song absolutely set in time and place, and therefore virtually uncoverable - into a five-minute-plus glam rock song with coked-lined backing vocals. There is something almost Showaddywaddy about it : all that butch posturing and leather jackets and Elvis covers. And then there is the third verse where he even supplies sound effects to literalise Dylan's metaphors :

I heard the sound of a thunder, it roared out a warnin' (rumble of thunder)

Heard the roar of a wave that could drown the whole world (wave crashes onto a beach)

Heard one hundred drummers whose hands were a-blazin' (fearsome snare drum fill)

Heard ten thousand whisperin' and nobody listenin' (vampy backing singers gossip amongst themselves)

Heard one person starve, I heard many people laughin' ("ha ha ha ha!")

Heard the song of a poet who died in the gutter ("aaah!")

Heard the sound of a clown who cried in the alley

And then comes the strapline, Ferry doing his best to imitate some calmly railing, ranting Nazi general, but always stamped over by his dominatrix backing singers:

And it's a hard ("hard!"),

and it's a hard ("hard!"),

and it's a hard

hard

hard

hard

And it's a ... hard rain's a-gonna fall.

And on that last "fall", the coked-up vamps suddenly turn into angels : angels who shower you with pure AOR shimmer.

The whole effect is somehow one of extraneity : one can see why Dylan wrote "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall" : it has a message which the US government needed to hear. But why would Ferry have covered it? And why in this way? Well : if you're in the wrong mood, Bob Dylan can be foully irritating, especially his early stuff. It is not so much that he is didactic - his visions are usually baroque enough to avoid preachiness - but his songs are so ascetic, so grey. They appear to sacrifice essence for all-out substance, and as such feel rather forced. Ferry does the opposite. He comes across as pure surface, and comes up with a version far more imbued with meaning than the original.

Aside from "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall" and "These Foolish Things" itself - a cover version so utterly transcendent, that it would need a separate post to examine its delights sufficiently : suffice it to say, it is the definitive version of the song - the most interesting tracks are the ones written or originally sung by women.

On "River of Salt" Ferry quivers like an abandoned child. On "Don't Ever Change" (by Goffin and King, notorious for their songs of sado-masochism), he starts to take on the Diane-Betty role : his girlfriend doesn't know the latest dance, but knows the time to make romance. Life is sweet, though only (in Ferry's version, though certainly not in Buddy Holly's) because no other guy can fuck her quite as heartily as he might imagine he does. And on the truly absurd version of Lesley Gore's "It's My Party," Ferry becomes jealous of Judy because Johnny's supposed to be his. Nobody, on listening to the whole album, would suspect Ferry of simply forgetting to alter the gender pronouns of Gore's original - not because of any latent homosexuality, but because there is a vein of sexual competition-cum-repulsion to women. He wants Johnny so that Johnny can't have Judy.

This is masochism par excellence : each of the three mother figures which Deleuze suggest variously make up the female masochist ideal are present. The destructive haetera is ever-present : impulsive in love, equal to men only insofar as she can destroy them. The pure sadist is Judy : she enjoys hurting others, but only with the aid of another, obscene male figure. And the intermediate "ideal" is there in "You Won't See Me," labelled by one of McCartney's greatest lines : "I wouldn't mind if I knew what I was missing."

In Leopold von Sacher-Masoch's The Divorced Woman, Julian feels an urgent need to see his mistress naked for the first time ; but this is quickly followed by an almost religious feeling of veneration, without any sexual urge. This is how fetishism works, and These Foolish Things, for those that like that sort of thing, could well function as the ultimate fetish object. That aside, it is a materpiece of post-modernism - perhaps the best that pop has produced.